Prior to World War I, as corporate America experienced growth, the male dominated fields of secretaries and typists set in motion an interesting dynamic: company owners – men – would look to their male secretaries in a way that resembled a father and son relationship, giving the new, young, white collar worker an opportunity to rise in the company. World War I changed all of that. As male secretaries left their jobs to enlist, women took their places. But when women dominated the pool of administrative staff, that father/son relationship changed to one of husband and wife. White collar became pink collar. Female secretaries became an extension of the emotional labor support that men enjoyed in the home.

Change to Women as Secretaries & Assistants

And who do you think provides all the unpaid labor at the office that lubricates the more emotional contact between people? Yup. Women. That includes dealing with a slate of “office housework”: buying and sending around the sympathy card at the office, arranging for the birthday cakes and setting up the parties, and making sure get-well cards are distributed, maintaining the office social calendar, stocking the refrigerator, making coffee, clearing common areas, scheduling meetings…. Sound familiar?

On the other end of the spectrum were the executive secretaries. These more autonomous, highly paid assistants to corporate bosses increasingly came to be seen as “office wives,” the epitome of a woman’s office career aspirations. With large numbers of women entering office work, companies created two paths for mobility: a female path with what we would call today’s “glass ceiling” and a male path. While young boys might start as an office clerk with hopes of becoming vice president one day, young girls could only realistically hope to be the vice president’s secretary.

More Change after WW2

After World War II the number of women in the paid workplace rose. Flex time did not exist. There weren’t ways to accommodate the growing number of women in the workplace and the fact that women are still doing all the primary caregiving and emotional labor at home. Seriously, not much has changed in the last 70 years since the end of World War II.

Consequently, if the paid workplace is not designed for women, yet culturally if we expect women to keep the home fires burning, then it makes perfect sense that women are exhausted and the workplace exacerbates the burden.

Mothers and the New Workplace

And for mothers, as always, there is the constant juggle between the unpaid workplace and the paid workplace. When I think about the fact that the paid workplace was never designed for women, a lot of it has to do with logistics. The hours of the traditional workplace don’t coincide with the hours of the school day. This is evidenced most clearly by the clock-in, clock- out hours of the typical nine-to-five job. It never corresponded to the typical eight-to-three school day. Not to put too fine a point on things, but when a woman asked for a hybrid or flex schedule to accommodate her second (or 3rd!) shift at home, her request was typically viewed as,- you guessed it – not being committed enough to the job. Although work from home (WFH) is now what we do, the closure of schools and day care centers ushered in the nation’s first-ever “she-session.”

In a Fall 2020 interview about the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic on working women, C. Nicole Mason with the Institute for Women’s Policy Research said, “What we have is a system made for men that assumes 100% availability for work, unencumbered by care-taking responsibilities or demands because there is a woman at home to take care of those responsibilities.”

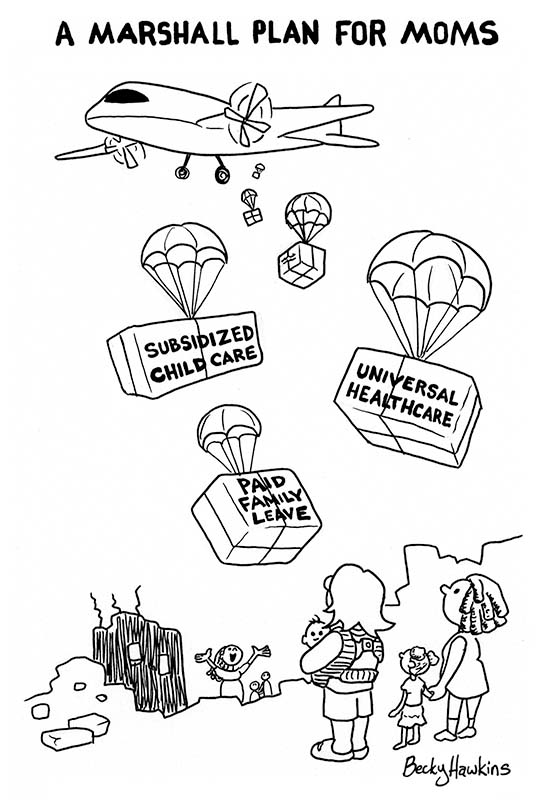

The Marshall Plan for Working Mothers

Reshma Saujani, is a thought leader on the topic of gender inequity – both at home and in the paid workplace. In 2020 she founded, the Marshall Plan for Moms – an organization committed to policy change and fighting for workplace equity. In a recent interview she describes “mom guilt” where the two worlds of “perfect mom” and “ideal worker” smash right into each other creating layers of anger, frustration, worry, and burnout. “To get rid of mom guilt, we not only need to change expectations around what both of those things mean, but also provide the structural supports to make motherhood easier—like childcare. Not just so we can go to work, but so that we can go anywhere or do anything for ourselves.”

Toward a Solution

Much of women’s burnout can be traced to the crushing weight of emotional labor carried from home to the paid workplace and back again. Wrangling our loved ones at home to share the burden of household management can be challenging, especially when the desire for change usually come from one person (the woman!). But the paid workplace is different because there are more people involved who actually want change and who are ready, willing, and able to participate in sharing the burden of office “housework.”

Managers and company leaders need to be able to recognize burnout in their teams, how the burden of invisible, unpaid labor is landing on particular employees, and put thought and resources into finding solutions. It’s time to imagine a workplace designed for women.

Kristin Hoppe writes about creating social equity in the workplace by employing a variety of factors and initiatives to eliminate burnout starting with recognizing good work by looking at pay equity across the board. Financial incentives and outward recognition for solving problems or closing a big sale show team members how much their contributions are valued.

In the physical or virtual office setting, researchers find no career benefits to performing office housework described as “the administrative tasks, menial jobs, and undervalued assignments, women are disproportionately given at their jobs” with further evidence suggesting that not just women, but women of color will frequently be called upon the carry the load.

If the budget allows a manager should be hired who is specifically tasked with what the uninitiated call menial or low-level. Granted, these tasks (filing, phones, organizing common areas, note-taking, etc.) are each easy to do. But managing them in addition to the work already being done by the employee. That’s the rub – we hire folks to do a job, and also confer upon them the expectations about performing these additional “menial” tasks. If they have to be performed, they aren’t menial.

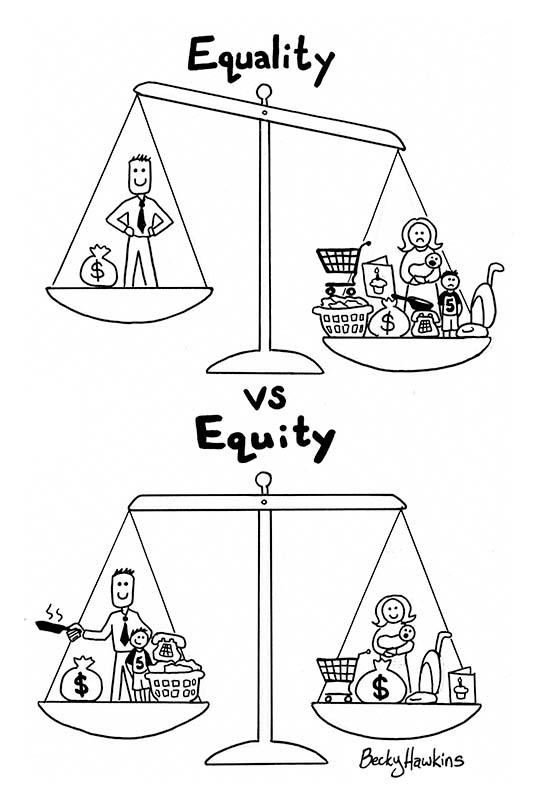

Equality & Equity to the Modern Workforce

Leaders in smaller companies work with employees to develop the long list of tasks that someone has to do – and then divide and and rotate the tasks through the company. Create a Google document for the tasks and everyone – management included – takes a turn with all the unpaid and invisible labor necessary to keep the office running at an optimum level. When management is involved in taking on administrative tasks, they’ll be less likely to exploit their direct reports with so-called “menial” tasks and may instead take them on themselves.

For remote workers, employ similar strategies. Managers must be trained to recognize when a disproportionate share of office housework lands on the shoulders of one person. Rotate the tasks and redistribute the weight of the work.

Our current WFH home life is a new archetype for parents and ushers in an additional way to create more social and gender equity in the workplace as well as to provide value to your team. Listen to your employees who request flex time or a hybrid schedule. Encourage parental leave for both parents. Provide childcare stipends, and as Kristin Hoppe so correctly points out, to “accommodate significant life transitions,” so meaningful in every family. If we can take these steps, we will find that we have created a workplace truly designed for women.

Regina F. Lark, Ph.D.

June 2022